Forrest Behm

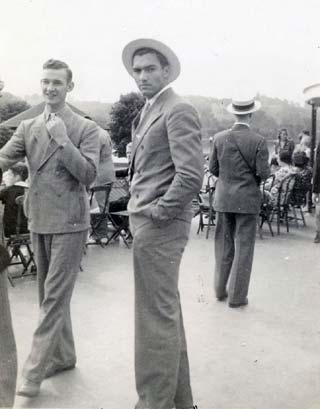

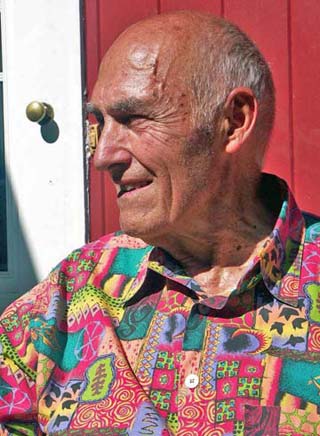

Forrest Behm played at Nebraska from 1938-1940 and was a member of the 1941 Rose Bowl team. He was an All American and All Big 6 in 1940. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1988. (Here are two pictures from that weekend 1, 2.) He was the featured player on the game ticket for the Southern Miss game on Sept. 11, 2004. Here is a picture at that game with Jim Rose and Adrian Fiala after a pre-game interview. These interviews are being done in conjuction with the Bob Terrio Classic. This interview was done by David Max on May 10, 2005.

DM: Where are you from originally?

FB: I was born and raised in Lincoln, Nebraska. All my schooling took place there until I left Lincoln to go to Harvard Business School, just before WWII.

DM: That is obviously how you knew about the Nebraska football team.

FB: Yes.

DM: Did you graduate high school in Lincoln?

FB: Yes I did, and I ended up graduating in 2-1/2 years. It was a big surprise when the principal called me in and said, “Look you’re going to graduate next week.” I said, “No, no, no, I don’t graduate until June!” He said, “No, you’re going to graduate now. You know, with this drought and depression we’ve got, we can’t afford to keep you in school. You’ve done everything you’ve been asked to do for two years and a lot more than that, and your grades are almost all 100’s. You’re going to graduate in a week.” So that’s what I did. I left high school and went to work for the Bell Telephone Company up in South Dakota, sometime in January, 1937.

DM: How long did you work in South Dakota?

FB: I worked eight months there.

DM: When did you start school at Nebraska?

FB: Well, let’s see, I’m now 85 and I was born in 1919 and I was 18 when I started college, so it was September, 1937.

DM: How did you end up playing football?

FB: Well, it’s kind of a roundabout story. I had a terrible burn on my right leg when I was five years old, and I was a cripple from five until about nine, on crutches and wearing braces and all that sort of thing.

DM: How did it happen?

FB: I was playing with a friend in a dry field, and we accidentally started a fire. I was trapped in the flames, and might have died right then, except a painter was driving by on his way to some project, and saw me. He grabbed a painter’s cloth and wrapped me up and carried me home. You can imagine how my mother felt when he brought me in with skin literally dripping off my leg! I had burned my leg from ankle to hip and the doctors wanted to amputate it right away, as there were no antibiotics in those days, and nothing to fight infection. My father told them no, they were not going to amputate, he would find another way.

From the first day, he gave me a piece of pine wood to bite on, like in the old days – biting the bullet--, padded his hands with cotton, and started to massage and work the leg. And he did that for 5 or 6 years, sometimes twice a day. Then, as the leg got better, he put me through calisthenics, deep knee bends, the works. Then he put me on a bicycle and made me learn to ride.

I remember very clearly the time I came home from grade school and told my father I had been beaten up by the big boys in the class. He showed me how to fight with a brace on my leg and crutches, and I didn’t have any trouble from then on. That took care of the problem. Anyway, my father and my mother were really heroes in this story. They even had to teach me at home for some time until I was able to go to school. I have a picture of myself when I was 11 years old, and you can see the scar on my leg, so apparently it had healed enough by that time that I was able to walk without crutches.

I used a cane now and then when I went to high school, but by that time what I really wanted was to play basketball. I was tall, 6’4”, but so clumsy because of the bad leg that when I went out for the team, I couldn’t make the varsity – they put me on the sophomore team. We played in church basements and warehouses, but I didn’t care. At least I was on the team, and that’s where I wanted to be. Then my junior year, I went out for basketball again – same thing. They put me on the sophomore team. So when my senior year came around, I went to the coach and asked, “ Is there any chance for me to get on the varsity?” He said, “None whatsoever!” So I went to the football coach – his name was Neal Mehring; he played football at Nebraska and so did his brothers – and asked if I could go out for the team. He looked me over and said, “Yeah, you can come out.” So I sat on the bench that year, but I got to practice and I played in a couple of games, so that’s what started me on football. Neal told me several years before he died, about 8 years ago, that I was the only player he ever allowed to come out in his senior year. I never would have played football if that hadn’t happened.

DM: So you never would have played if you hadn’t gotten kicked off the basketball team!

FB: Right! Now when I left school in my senior year, this leg still wasn’t in that great of shape, but I did construction work, which consisted of digging holes and tamping poles in, cutting brush and clearing right of way and stringing wire – perfect conditioning. As you know, back in those days, you didn’t lift weights, you didn’t do any special exercises, except just stretching. But now I had this hard work to do, and that worked out very well. Anyway, when I came back to Nebraska, one of my buddies said, “Come on, let’s go register for the University.” At that time, it cost $35 a semester for tuition. We had saved that money up, so we had the money to go to school. He said, “Let’s go down and register and, while we’re there, why don’t we register for football?” Lee Farmer was his name, hell of a guy, he’s down in Tucson right now, great athlete. He shot his age in golf, which will tell you how great an athlete he is. And I said, “Lee, I don’t know how to play football. I sat on that bench for a whole year in high school.” Lee said, “We’ll have a lot of laughs!” So I went out for football.

When I got there, the coach said, “Get down to Floyd Bertoff and get your equipment.” Floyd gave me the stuff you get for that type of assignment, and then he said, “What size shoes do you wear?” I said, “15.” He didn’t say anything – went over to the coach, came back and said, “You can’t come out.” I said, “Why can’t I come out?” He said, “We can’t afford to buy you shoes.” I said, “What if I buy my own shoes?” He went back to the coach, came back again. Said, “Yeah, if you buy your own shoes, you can come out.” I made the first team of Nebraska in my sophomore year in my own shoes.

DM: That was 1938?

FB: Yeah, that was 1938. And I played on the first team and I started most of the game that year, with my own shoes! Anyway, I did really well in my junior year but it was in the middle of a very serious Depression – Depression started in 1929 and lasted until the start of WWII. In 1939 it got really, really bad – like 30-40% unemployment. It was very hard to get a job. I couldn’t get into the telephone company, they were laying people off, so I went to the coach and said, “I’m not going to be able to come back to school. I have to earn $70 plus enough for my clothes. I can live at home, but if I don’t get my clothing money or the $70 for tuition, I’m not going to be able to come out.” He said, “We haven’t got any jobs, we don’t have anything for you to do.” I was thinking, well that’s the end of my football career because I’m not going to be able to go to school, but I read in the paper just a couple of days later that they were hiring people to shovel concrete in a road construction job -- what is now called the Cornhusker Highway that runs around the northern part of town. I went out and applied and they gave me the job, which was to stand in the pit where they dumped the concrete from the big mixer, spread that concrete out, tamp it into place, and keep the blade of the spreader wet with concrete. If the pile got too heavy, we’d shovel it away from the spreader. We shoveled for six hours straight, with no relief at all. If we had to pee, the other guy had to do all the shoveling while we peed. So it was right straight through.

Then when I finished with that job, I stacked 100-lb. bags of sugar down at the terminal warehouse, which used to be right down near the University. At the terminal warehouse, there were train loads of sugar that would come in from the beet fields in western Nebraska. I don’t where the sugar was manufactured but it came into this terminal warehouse and the boxcar would arrive with bags stacked right up to the ceiling. We had to drag those 100-lb. bags out and put them on a three-wheel cart, take them into the warehouse, take them off the cart and stack them up to the ceiling, which was 18 ft. high. We stacked them all the way up to the top – didn’t have any equipment to get there. We’d stack the bags up to one level and then toss them up to the next level. Well, you can imagine the conditioning I got from all that work. When I reported for practice in my junior year, Biff Jones wouldn’t let me practice. He put me down on the playing field with a manager and we threw the ball around, passed the ball, ran a little bit and then went down to the swimming pool and swam for 45 minutes. That was my two weeks of practice in my junior year. I was so strong – it was unbelievable how much strength I had. That’s what kids do now when they lift weights, but we didn’t lift any weights in those days. I often think that’s one of the reasons I played so well in my senior year.

DM: You mentioned a story about Coach Schulte.

FB: Yeah, he was the track coach and when I got to school he was in a wheelchair, I don’t know if it was spinal meningitis or what it was but he was in a wheelchair and he was sitting on the sidelines – I didn’t know who he was, but shortly after I got a pair of shoes I was running down the field – one of the things we did back then, you’d line up and you’d have a couple of blockers down the field and you’d have two punt coverers and the ball would be snapped and the kicker would kick and we were on our way down the field and the blocker would try to stop us, so the ball carrier down there would take the ball and run – it was a good experience for all of us. We had been doing that drill a couple of times and I had been running down the field about the second time I’d done it – as I was walking back I heard this big voice – “hey, you, kid”. I looked over and here was this good looking man, but you could see the pain all over, you could just tell by looking at him. He said, “come here, kid”. And I went over and he said, “kid, you run like a cow in the mud, I’m going to teach you how to run”. And he did and it really was one of the many things that people did to make my career successful. You know, being timed on a couple of occasions running 100 yards on the field, on the grass, against the stop watch, my best time was 11 seconds, which was pretty damned good with a full uniform on. The track coach heard about that and said, we can put some shoes on him and maybe he can run something for us. So they ordered some track shoes and I put them on and I ran, guess what, 100 yards – 11 seconds. It didn’t matter what kind of clothes I was in. I was just a big lumbering old locomotive – get outta my way, it’s gonna be 11 seconds.

Okay coming back to Schulte - he actually showed me how to stand and how to move – my right foot, because of my scarred leg it turns out a little bit and he showed me how to run with that. And I galloped and I got away from galloping and he was a very helpful man. And, of course, I quickly learned that he was the great Schulte – I think he was the Olympic track coach for the United States for one or two Olympics.

DM: I’ve always heard the name Schulte Fieldhouse, but I never knew the story behind the individual.

FB: Everybody that worked and competed in his age, said he was a real leader.

DM: So when you first met him, he was in a wheelchair.

FB: Oh, yeah, I’d never met him before. I didn’t know who he was. I don’t even know the years he was in the Olympics – I don’t even know if that story is true or not.

DM: Did you play in your junior year?

FB: I played every game.

DM: So you just had to do the conditioning for two weeks to get back on the team?

FB: Yes -- maybe it was ten days, but it was a short period of time.

DM: What position did you play?

FB: I played right tackle, offensively and defensively, and linebacker.

DM: What did you like best – offense or defense?

FB: Nobody has ever asked me that. I guess I don’t really know. I liked all kinds of football. I enjoyed the whole game. Didn’t matter where I was as long as I was in the battle.

DM: Fred Meier was your teammate and he was a center on the offensive line and he also played linebacker, so you guys were linebackers together.

FB: Whenever we ran a five-man line, I was a linebacker. When we played the regular six-man line, Freddy Meier was always a linebacker on defense, but I was only a linebacker when we had a five-man line or some special freak type of defense. We played seven-man line, six-man line and five-man line. Those were our defenses.

DM: Do you remember any particular games, a regular season game, that sticks out in your mind?

FB: The game that sticks out in my mind was a game against Minnesota in my sophomore year. I remember a player on the Minnesota team by the name of Ed Widseth. He unfortunately played opposite me. He was an all-American tackle and a wonderful player. He beat the hell out of me. He and his buddies just beat all of us up. I came out of that game, got myself patched up and went to a hotel room in St. Paul. I’m lying in the room with a broken nose and a twisted knee, generally beaten up all over my body, and I said, “What the hell is this football game? I don’t know whether I want to play this anymore!” But I did, of course, and nobody in the next three years beat me up. Certainly not like those guys did.

DM: Did you win that game or did you lose?

FB: We lost it by a touchdown, I think.

DM: Tell me something about when you made a road trip, like to Minnesota, did you go by train or by bus?

FB: We always traveled by train.

DM: When you played Minnesota on Saturday, when would you leave Nebraska?

FB: It was 500 miles – we’d do it overnight. I think we left on Thursday night and then we’d come back on Sunday.

DM: Tell me about the Rose Bowl game in your senior year. Do you remember how long that trip was?

FB: I would guess it was two days getting to Arizona where we practiced. I think we had five or six days near Phoenix in a place called the Camelback Inn. It’s still there – I saw it a couple of years ago – gorgeous place now – it’s almost in the middle of the city. When we were there it was way out in the country.

DM: So when you went to the Rose Bowl you stopped in Phoenix and practiced for a few days there before you went to Pasadena.

FB: Yeah, there was no way we could practice in Lincoln. It was snowy and cold.

DM: What do you remember before the game – did you do any sightseeing?

FB: They entertained us very well. We went to movie studios, we got to meet actors and actresses. I remember meeting Robert Taylor and a lot of beautiful women that were there. To tell you the truth, I wasn’t very interested in that. I was out there to play football.

I never missed a game when I played. I played every game for three years and when I got to Phoenix I was in fantastic physical shape. I felt strong, felt good, I didn’t have anything wrong with me. Then I was stretched out on the sideline when one of the players was rough housing with another player, stepped backwards and put a cleat right in my hip joint. It really was a very bad injury. I could stand and walk carefully, but I couldn’t put any pressure on that leg or I’d collapse, so I didn’t start the Rose Bowl game. Herndon did. I filled in for Herndon half of the game but they kept me out when things got a little grim because I was “playing on my newspaper clippings.” I’m not sure they ran very many plays at me – I don’t remember the game at all. I was just glad to get it over with. To me the Rose Bowl was an absolute disaster because I was injured. I wasn’t able to play to my ability. Maybe Herndon did a lot better job than I would have if I were in there, but I didn’t get to start the game.

DM: But you did play for half the game. What were the substitution rules – were there any regulations as to how many substitutes you could have?

FB: Very limited. If you came out in a quarter, you couldn’t go back in that same quarter. There wasn’t unlimited substitution until long after I quit playing football.

DM: During your three years as a starter on the varsity, during a 60-minute game, how many of those 60 minutes would you play?

FB: I would guess that it would be typical in a game for me to play at least half of the time, maybe three-quarters.

DM: Other than being injured in the game, what do you remember about the game?

FB: I think there were two things that impressed me about that game – one was the quality of the Stanford team. They had four back-field men that all went on to be successes as pros. They had Stanley, who was a fullback. They had Albert, who was a quarterback. They had four absolutely terrific back-field men and the T-formation that they ran – that was the first time we’d ever seen a T-formation -- was very baffling to me. But we did extremely well against it. I don’t think their defense was as great as their offense. That offense that they had was magnificent.

DM: Do you remember how full the stadium was?

FB: It was absolutely sold out. When I came out of the dressing room in any game I’d ever played up till then, I didn’t know there was a crowd there, I didn’t know anything but the football field. I’m sure the emotion and drive of any game affected me, but I wasn’t aware of it. But in the middle of the Rose Bowl game, when I was on the field, I heard this great cheer that Stanford has that starts out by saying, “Give ‘em the axe, the axe, the axe, give ‘em the axe, the axe, the axe” – they start very softly, 100,000 people all saying, “Give ‘em the axe, the axe, the axe,” and they get to the end of the progression of sound and every one of them is screaming at the top of their voice, “GIVE ‘EM THE AXE, THE AXE, THE AXE.” And I stopped and looked at the crowd – only time I ever did.

DM: What was it like when you came back to Lincoln after the game – were there any fans there to meet you?

FB: We came in to Union Station in Lincoln – it was a mob. They really were wonderful. We had a huge delegation of people to meet us, and I was embarrassed because we lost – we weren’t supposed to lose that game. The whole experience, it started to go sour when this guy damaged my hip. I don’t think to this day he even knows he did it.

DM: Was the Rose Bowl game the last game of your career?

FB: Yes, that was it.

DM: After that, you went on and graduated from Nebraska?

FB: I graduated from Nebraska and I got a fellowship that I used to go to Harvard Business School. My wife, Betty, and I were going to get married, but we didn’t have any money at that point so we decided I’d finish my education and then we’d get married – that was the fall of 1941 when I went to Harvard and of course war was declared December 7th of that year and a couple of weeks after that, I was in the Army. At Nebraska, I had been a Lieutenant Colonel of the ROTC and I had won the Field Artillery Association medal, so I was immediately in the Service.

DM: How many years were you in the Service?

FB: Almost five years. I think it was about three months short of five years.

DM: When you got out of the Service, what did you do?

FB: Went to work for Corning Glass Works.

DM: Did you go back to school at Harvard?

FB: I went back to see a couple of my professors and the Dean, and they all recommended that I not go back to school. By that time I had a baby and a wife and they thought I’d be able to get a good job. I spoke with George Abel a couple of years before he died – he was one of the great football players on our team and one hell of a guy – and he went to Harvard Business School after WWII. He was being interviewed there by the Dean of the college and the Dean said, “Oh, you’re from Nebraska, do you know Forrest Behm?” He said, “Yes, I played football with him.” The Dean said, “I hope you’re as good a student as he was, because he had the highest first year average of anybody that ever came to this School.”

DM: So you went to work for Corning and you never went back to school?

FB: No, I never did.

DM: How many years did you work at Corning?

FB: 41 years.

DM: When did you retire?

FB: I technically retired In December, 1986. As an officer and a member of the Board, I had to retire at 65. But they wanted me to stay on as a “consultant” and do some things that had to be done. Jamie Houghton, the Chief Executive Officer, said, “We’re going to retire you just like we must, but you’re going to stay in the same office, you’re going to have the same secretary, and I want you to help me change the company’s management practices.” So I stayed for three years with Jamie Houghton helping to institute total quality management, and instead of retiring at 65, I retired at 68.

DM: Do you still live in Corning, New York?

FB: In the same house I built 50 years ago. You know I’m a Nebraskan, so you have to have land, right? In 1960, I bought 600 acres of land back in the woods here. The country around here is all hilly and wooded. Part of the farm is, I think, 1800 feet in the air. I was planning to build a house there and move out of this house -- I had it all ready to put it out for bid in 1971. But then, in 1972, we had the worst flood Corning ever had, which wiped out 3,000 homes. It was a very damaging flood. The whole process of repairing the damage to the buildings took up all the construction labor, and nobody would bid on my house. It took ten years for them to get enough work done for anybody to decide they were willing to bid on the house and by then I didn’t want to build it any more. The kids were grown up and had left home. But I still have the land. I’ve sold some of the timber and they’re drilling for gas up around there now so maybe I’ll get some money from that. This is beautiful country here in Steuben County.

DM: Do you have any newspaper clippings or anything from your playing days that I could get copies of?

FB: Yes, I think there’s one article that was written by a newspaper guy down in Kansas City about my burn. A beautiful article about my father and my mother getting me through that difficult time – I’d love to have you use some of that.

I’d also like to include my wife’s obituary. Betty was a Phi Beta Kappa at the University of Nebraska – she was the only girlfriend I ever had. She tried to get rid of me by getting me dates with other members of her sorority house. I finally said, “Don’t do that anymore.” It took me a long time to get her to be really seriously interested in me. We only started to go steady in our junior year. Back in ’37, my buddies had said, “Hey, let’s go up to the Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota and fish.” We were the four horsemen, Freddy Meier, Leroy Farmer, Warren Day and me. They set up this trip and wanted me to come with them so I said, “Sure, I’ll do it.” I didn’t know they were going up to Betty’s family’s cabin in Cass Lake, Minnesota. When I got in the car, and we were on the way to Minnesota, I asked, “Why are we going to Cass Lake?” They said, “Our girlfriends are up there and we want to stop and see them before we go fishing.” When we got there, I found out Betty was there and she didn’t have a boyfriend with her so she was stuck with me for two days. We swam and we canoed and we took long walks and got very well acquainted and when we got ready to leave I said to myself, “That’s the woman I’m going to marry.” She was my only girlfriend and we were married 61 years. She died six months ago. Click here for a picture from that fishing trip.

DM: Was that trip to Minnesota the first time you had met her?

FB: No, we met in junior high school. Back in those days the girls would plan a party and they’d say to their girlfriends, “Who do you want me to invite to come with you?” Then they would set the dates up and the parents would drive us to the party, then pick us up and take us home. A friend of Betty’s, Gwenny Orr, invited Betty to come and asked who she wanted to have as her partner and I was picked. So our first official date was when we were 14 years old. I’m really proud of Betty. She was on the County Mental Health Board, she co-founded a local arts center here called 171 Cedar Street, and was the first Treasurer. She was the Choir Director of our church here in town and had a junior choir of 40 children that sang every Sunday. She was often told that you couldn’t do that with children and she said, “Maybe so, but they’re doing it every week!”

DM: I met your son, Greg, after the game you attended last fall. Here are two pictures - 1, 2.

FB: Were his sons with him?

DM: Yes.

FB: The big boy is going to be a freshman at Nebraska this year. His name is Nicholas. I’m very fortunate: I have four wonderful children and nine grandchildren – I love them all!

DM: Forrest, thank you for sharing your Husker memories.

Listed below are more links about Forrest Behm and the 1941 Rose Bowl team. If you would like to send Forrest a comment about this interview or suggest another link please send it to this email.

Rose Bowl Program (All 24 pages), 60 year reunion questionaire 1, 2, 3, 4, 60 year picture, 25 year reunion 1, 2, 3, NETV, teammate Fred Meier interview.